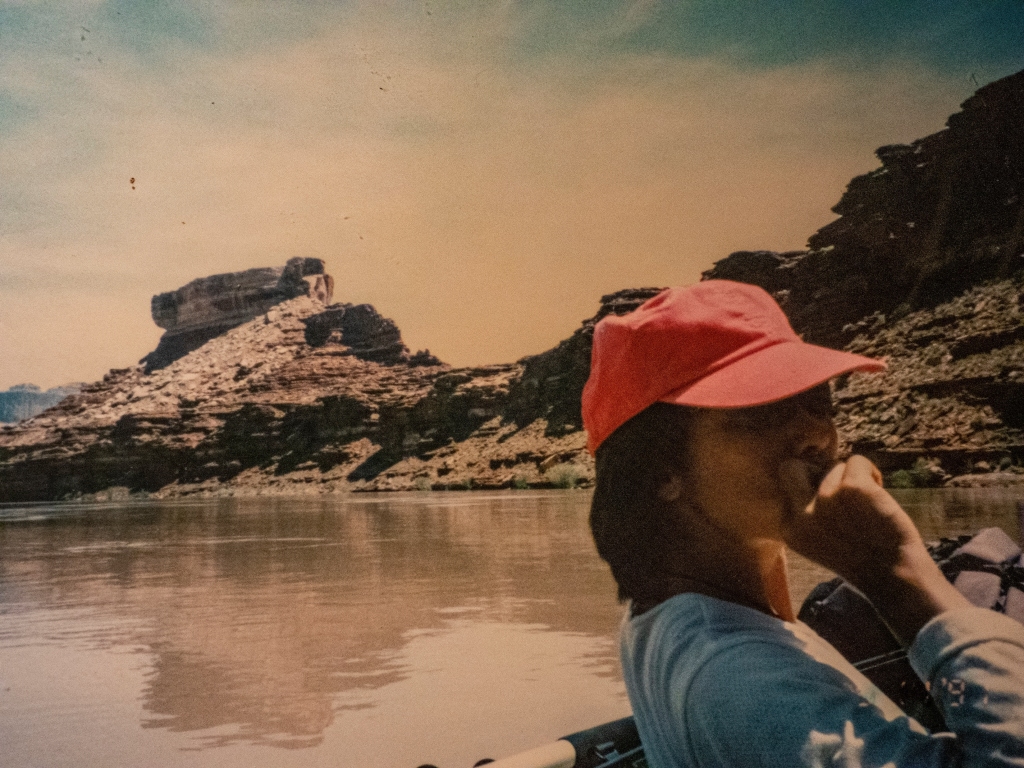

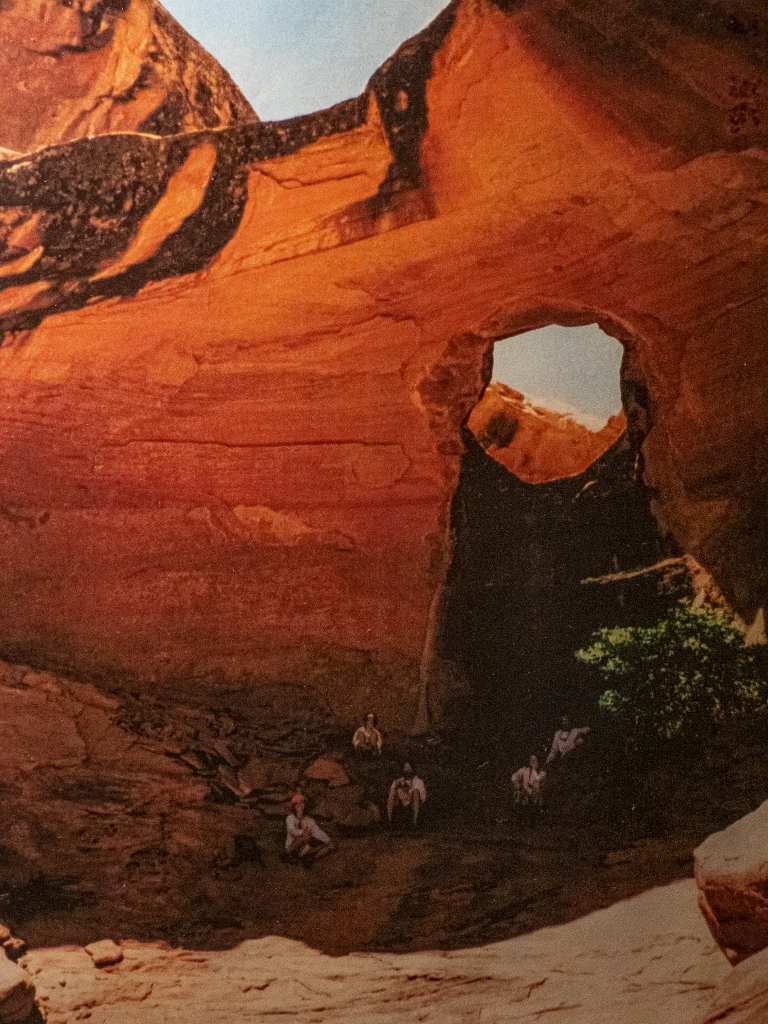

Last week I read an excerpt from the autobiography of Bede Griffiths, and Englishman whose profound experience of Nature led him to first become a Christian monk and then to immerse himself in Hindu spirituality in India. I suspect many of you who feel my images have had the experience of a profound witnessing of Natural Beauty. You will resonate with this excerpt, and I hope it will remind you of the importance of that experience, whether it involved the awe of big Nature like towering granite walls, giant surf, or huge trees in an old growth forest, or it was something small like a close visit of a singing sparrow, or the dew on a spider web. Such experiences are to be honored, and never forgotten, so we remain open to many more, and so allow them to shape our experience to life on Earth.

“One day during my lat term at school I walked out alone in the evening and heard the birds singing in that full chorus of song, which can onlu be heard at that time of year at dawn or sunset. I remember now the shock of surprise with which the sound broke on my ears. It seemed to me that I had never heard the birds singing before and I wondered whether they sang like this all the year round and I had never noticed it. As I walked on I came upon some Hawthorne trees in full bloom and again I thought that I had never seen such a sight or experienced such sweetness before. If I had been brought suddenly among the trees of the Garden of Paradise and heard a choir of angels singing I could not have been more surprised. I came then to where the sun was setting over the playing fields. A lark rose suddenly from the ground beside the tree where I was standing and poured out its song above my head, and then sank still singing to rest. Everything then grew still as the sunset faded and the veil of dusk began to cover the earth. I remember now the feeling of awe which came over me. I felt inclined to kneel on the ground, as though I had been standing in the presence of an angel; and I hardly dared to look on the face of the sky, because it seemed as though it was but a veil before the face of God.

These are the words with which I tried many years later to express what I had experienced that evening, but no words can do more than siggest what it meant to me. It came to me quite suddenly, as it wer out of the blue, and now that I look back on it, it seems to me that it was one of the decisive events of my life. Up to that time I had lived the life of a normal schoolboy, quite content with the world as I found it. Now I was suddenly made aware of another world of beauty and mystery such as I had never imagined to exist, excpt in poetry. It was as though I had begun to see and smell and hear for the first time. The world appeared to me as Wordsworth describes it with “the glory and freshness of a dream.” The sight of a wild rose growing on a hedge, the scent of lime tree blossoms caught suddenly as I rode down a hill on a bicycle, came to me like visitations from another world. But it was not only that my senses were awakened, I experienced an overwhelming emotion in the presence of nature, especially that evening. It began to wear a kind of sacramental character. I approached it with a sense of almost religious awe, and in the hush which comes before sunset, I felt again the presence of an unfathomable mystery. The song of the birds, the shapes of the trees, the colors of the sunset, were so many signs of this presence, which seemed to be drawing me to itself.

As time went on this kind of worship of nature began to take the pace of any other religion. I would get up before dawn to hear the birds singing and stay out late at night to watch the stars appear, and my days were spent, whenever I was free, in long walks in the country. No religious service could compare with the effect which nature had upon me, and I had no religious faith which could influence me so deeply. I had begun to read the romantic poets, Wordsworth, Shelly, and Keats, and I found in them the record of an experienc like my own. They became my teachers and my guides, and I gradually gave up my adherence to any form of Christianity. The religion in which I had been brought up seemed to be empty and meaningless in comparisson to what I had found, and all my reading led me to believe that Christianity was a ting of the past.

An experinece of this kind is probably not at all uncommon, especially in early youth. Something breaks suddenly into our lives and upsets their normal pattern, and we have to begin to adjust ourselves to a new kind of existence. This experience may come, as it came to me, through nature and poetry, or through art or music; or it may come through the adventure of flying or mountaineering, or of war; or it may come simply through falling in love, or through some apparent accident, an illness, the deth of a friend, a sudden loss of fortune. Anything which breaks through the routine of daily life may be the bearer of this message to the soul. But however it may be, it is as though a veil has been lifted and we see for the first time behind the facade which the world has built around us. Suddenly we know that we belong to another world, that there is another dimensio to existence. It is impossible to put what we have seen into words; it is something beyond all words which has been revealed.

There can be few people to whome such an experience does not come at some time, but it is easy to let it pass, and to lose its significance. The old habits of thought reassert themselves; our world returns to its normal appearance and the vision which we have seen fades away. But these are the moments when we really come face to face with reality; in the language of theology they are moments of grace. We see our life for a moment in its true perspective in relation to eternity. We are freed from the flux of time and see something of the eternal order which underlies it. We are no longer isolated individuals in conflict with our surroundings; we are parts of a whole, elements in a universal harmony.”

—Bede Griffiths, from Winding the Golden String

“That mysterious Presence which I felt in all the forms of nature has gradually disclosed itself as the infinite and eternal Being, of whose beauty all the forms of nature are but a passing reflection.”

—Bede Griffiths, from Winding the Golden String

“O thou Beauty, so ancient and so new, to late have I loved thee, to late have I loved thee.”

—St. Augustine

Prints of all images available. Tomreed.com is being rebuilt and should be up by 5/1/23.

In the meantime the old site is still up at https://tomreed98.wixsite.com/photography